Lesson 2: A beginner's guide to Emily Brontë & WUTHERING HEIGHTS

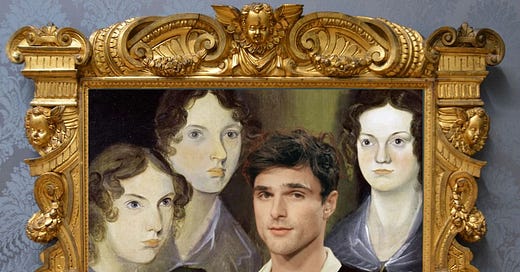

Should Jacob Elordi be Heathcliff? Plus, how would you feel if I said Emily Bronte punched her dog?

Today’s lesson looks at the context around the poet and novelist Emily Brontë, Gothic vs. Romantic vs. domestic novels, Liverpool’s slave trade, and Emerald Fennell. Let’s dig in, shall we?

The primary, maybe only, anecdote about Emily Brontë involves her punching a bulldog.

Her bulldog, specifically. With her bare fists.

In the biography The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857), published after the Brontë children had already passed, Elizabeth Gaskell includes the Bulldog Anecdote ™️ as an insight to Charlotte’s domestic life with her family. As quoted in Emily Rena-Dozier’s essay, Gaskell’s anecdote in full reads:

The same tawny bulldog . . . was "Keeper" in Haworth parsonage; a gift to Emily. With the gift came the warning. Keeper was faithful to the depths of his nature as long as he was with friends; but he who struck him with a stick or whip, roused the relentless nature of the brute, who flew at his throat forthwith, and held him there till one or the other was at the point of death. Now Keeper’s household fault was this. He loved to steal up-stairs, and stretch his square, tawny limbs, on the comfortable beds, covered over with delicate white counterpanes. But the cleanliness of the parsonage arrangements was perfect; and this habit of Keepers was so objectionable, that Emily, in reply to Tabby’s [the family servant’s] remonstrance, declared that if her pet was found again transgressing, she herself, in defiance of warning and his well-known ferocity of nature, would beat him so severely that he would never offend again. In the gathering dusk of an autumn evening, Tabby came, half triumphantly, half tremblingly, but in great wrath, to tell Emily that Keeper was lying on the best bed, in drowsy voluptuousness. Charlotte saw Emily’s whitening face, and set mouth, but dared not speak to interfere; no one dared when Emily’s eyes glowed in that manner. . . . She went up-stairs, and Tabby and Charlotte stood in the gloomy passage below, full of the dark shadows of coming night. Down-stairs came Emily, dragging after her the unwilling Keeper, his hind legs set in a heavy attitude of resistance, held by the "scuft of his neck," but growling low and savagely all the time. . . . She let him go, planted in a dark corner at the bottom of the stairs; no time was there to fetch stick or rod, for fear of the strangling clutch at her throat - her bare clenched fist struck against his fierce red eyes, before he had time to make his spring, and, in the language of the turf, she "punished him" till his eyes were swelled up, and the half-blind, stupefied beast was led to his accustomed lair, to have his swelled head fomented and cared for by the very Emily herself. The generous dog owed her no grudge; he loved her dearly ever after; he walked first among the mourners to her funeral; he slept moaning for nights at the door of her empty room, and never, so to speak, rejoiced, dog fashion, after her death.

Published almost a decade after Wuthering Heights’s publication, Gaskell eludes to a dark spirit within the novel’s author, a channel to the supernatural powers echoed in the setting of her story.

Was Emily a gothic witch: obstinate, violent, masculine? Or do we craft this reputation in the wake of her novel?

The only other sense we have of our author comes from her sister, Charlotte.

After her siblings—Branwell, Emily, and Anne—die within months of each other, Charlotte releases a second edition of Wuthering Heights. In Charlotte’s version, she lumps together paragraphs and alters punctuation, a correction to perceived missteps by the original publishers. “The books are not

well got up,” she writes her publisher, W.S. Williams.

She also includes a biographical notice of Ellis and Anton, her sister’s pen names. She gives her sisters posthumous credit for their novels and eulogizes them as their editor and sister. On Emily, Charlotte defends her sister as a timid, reclusive soul who doesn’t know the world and, therefore, blindly crafted a fictional world of evil. She describes her with a sharp eye of an editor:

In Emily’s nature, the extremes of vigour and simplicity seemed to meet. Under an unsophisticated culture, inartificial tastes, and an unpretending outside, lay a secret power and fire that might hve informed the brain and kindle the veins of a hero; but she had no worldly wisdom; her powers were unadapted to the practical business of life; she would fail to defend her most manifest rights, to consult her most legitimate advantage. An interpreter ought always to have stood between her and the world. Her will was not very flexible, and it generally opposed her interest. Her temper was magnanimous, but warm and sudden; her spirit altogether unbending.

In the margins, I wrote, oof. (Charlotte should meet the older sister from the “Please can I have the red crayon?” video.)

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Like her novel, Emily left no bones to pick through.

The same year Wuthering Heights was published and panned by critics, Emily caught tuberculosis. She refused medical treatment. “She sank rapidly,” Charlotte writes. “She made haste to leave us.”

She died, months after her brother Branwell and months before her sister Anne, in 1848. She was thirty years old.

But let’s go back to the beginning.

Forgive my Northern Attitude"

In 1818, in the wake of Jane Austen’s death and into the year Mary Shelley released Frankenstein, Emily Brontë was born as the fifth of soon-to-be six Brontë children.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to self-taught to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.