Lesson 7: A beginner's guide to Marcel Proust & SWANN'S WAY

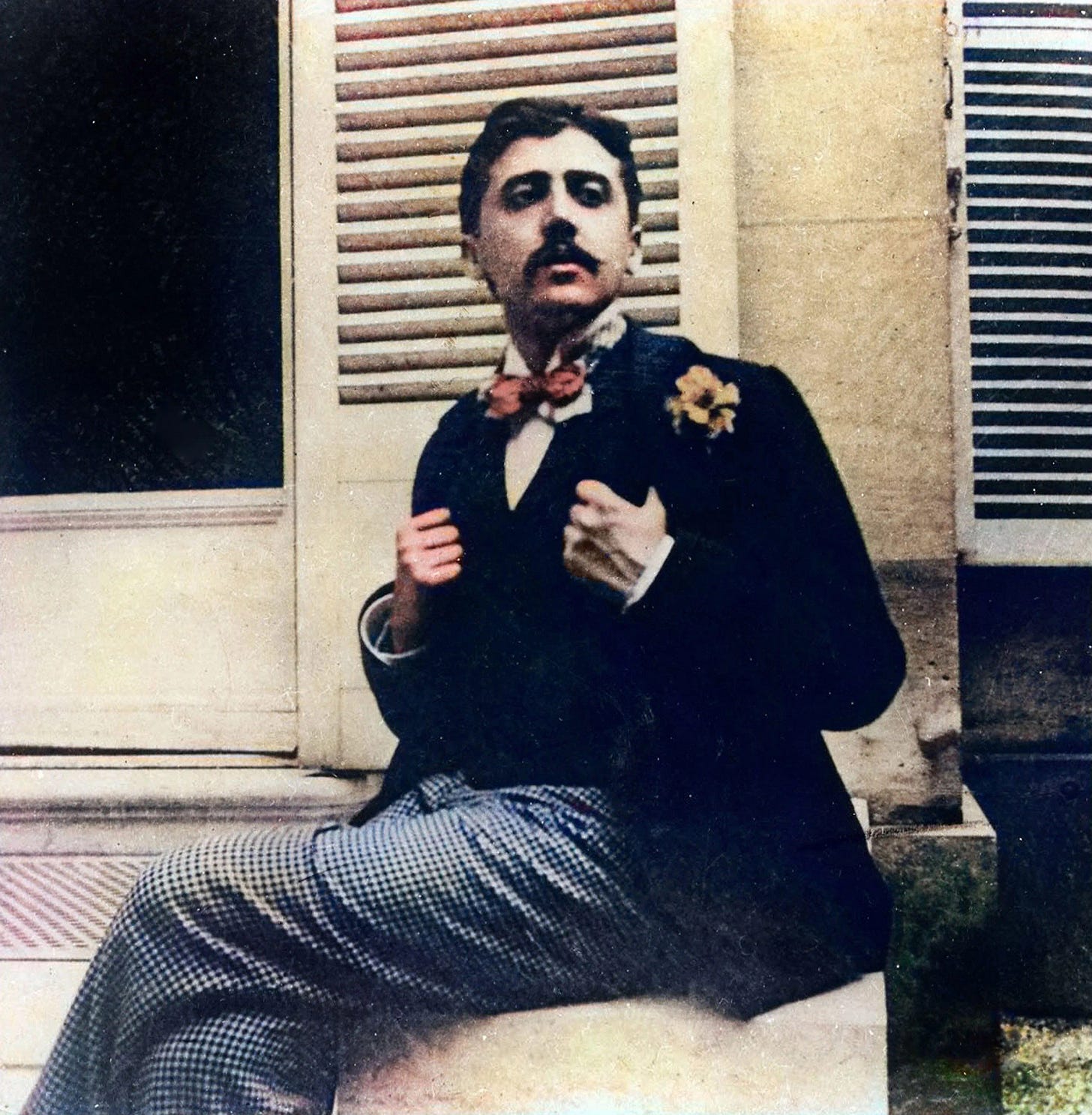

Proust lived searching for his past. When you search for his past, you find drama in the gaps.

You quickly collate the facts of Proust’s life into a sterile skeleton of bullet points:

He’s born in July of 1871. (A year like a ripple in pond. Does that number mean a thing? Does it mean anything when attributed to a bookmark in the chronology of our man-made history? No, not to you.)

His father is a French Catholic doctor, well regarded. His mother comes from a wealthy Jewish family.

He spent his childhood summers in the towns Illiers and Auteuil, which become the launchpad for his fictional Combray.

He attended an elite secondary school, Lycée Condorcet, where he maybe loved a female classmate, worked on the paper, befriended the children of Paris’s most prominent social figures. He enlists in the military for the year and likes the discipline before he enrolls at the School of Political Sciences for a degree in law, then a second degree in literature. He polishes off his educational journey in 1895.

His first published book, Les Plaisirs et les jours (Pleasures and Days), is a collection of short stories.

In 2019, 97 years after Proust’s death, French publisher Éditions de Fallois publishes the short story collection, Le Mystérieux Correspondant. Proust wrote them alongside the poems and short stories published in Pleasures and Days but withheld the stories from publication.

According to The Guardian, Proust specialist Bernard de Fallois, head of the publisher, found these stories in the 1950s, and the house published the stories after Fallois also died: “Proust is in his 20s, and most of these texts evoke the awareness of his homosexuality, in a darkly tragic way, that of a curse … In different ways, the young writer transposes, sometimes barely, the intimate diary he could not write.”

This, you think, is where the drama sets in.

But it doesn’t.

The biographical entries focus on his publication history, all the stepping stones toward the seven-volume opus In Search of Lost Time. Proust wrote a novel for four years he never finished. He offers legal assistance and petitions for Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer wrongly convicted and imprisoned under harsh conditions. He wrote a short story imitating the voices of his favorite writers, like Gustave Flaubert and Honoré de Balzac. He, alongside his mother, translated John Ruskin’s art criticism into French. Ruskin, a Romantic painter, railed against the Aesthetic critical conversation that suggested art exists for art’s sake. Instead, Ruskin stipulates that art serves as a foundation for social and moral thought, an idea Proust holds tightly.

In fact, Proust by the end of his life will take this idea to the farthest extreme. As he wrote in In Search of Lost Time, "The only life in consequence which can be said to be really lived—is literature.”

Does that mean the only way to know Proust is to read him?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to self-taught to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.