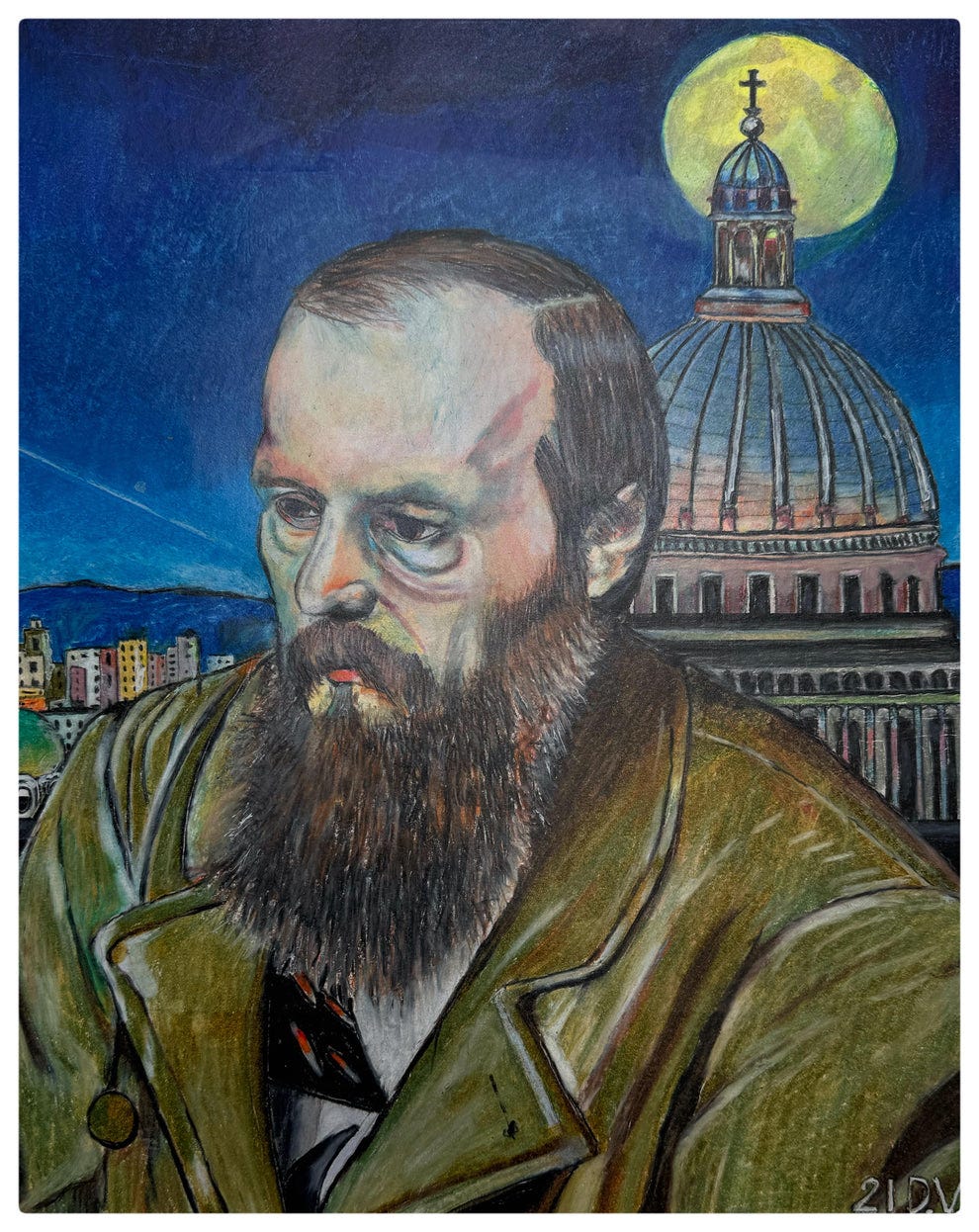

Lesson 4: A beginner's guide to Fyodor Dostoevsky & CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

Your guide to Dostoevsky, 1860s Russia, and CRIME AND PUNISHMENT.

On December 22, 1849, after eight months of a solitary confinement for a mild participation in a revolutionary group, Fyodor Dostoevsky is led to his execution.

He’s blindfolded and standing above a grave alongside another prisoner. The firing squad lined up behind him. Seconds before they expect to be executed, the guards tell the prisoners the tsar has granted them mercy via an exile to Siberia. The man alongside him is permanently traumatized, diagnosed and treated for insanity in the wake of his execution.

In a letter to his brother, Dostoevsky wrote,

“When I look back on my past and think how much time I wasted on nothing, how much time has been lost in futilities, errors, laziness, incapacity to live; how little I appreciated it, how many times I sinned against my heart and soul—then my heart bleeds. Life is a gift, life is happiness, every minute can be an eternity of happiness."

At the beginning of the 1860s, Dostoevsky will serve his ten-year Siberian sentence to a different type of Russia. Instead of Nicholas I, whose reign placed Dostoevsky in prison, he arrives in St. Petersburg under Alexander II’s rule, a time of optimism. return to Russia to start a magazine with Mikhail. His wife, then his brother, dies. He accrues significant gambling debts, enough to escape to Italy, Germany, and Switzerland. While living in the West, his Russian nationalism growing while living in Europe, he writes Crime and Punishment.

Crime and Punishment launches him as one of Russia’s greatest writers. His later book, The Possessed, will earn him the title of prophet for its accurate predictions of the Russian revolution of 1917, nearly 50 years after it was published. His last book, The Brothers Karamazov, will announce his greatness to Europe and the West, a region Dostoevsky sees as the inhibition to Russia’s ascension to greatness.

Before we go more into Dostoevsky, it’s important to understand the Russia he inherited.

Let’s go back 100 years in Russia

Over in America, when people discuss “Russian literature” as an academic field, I take it to mean this renaissance of 19th century Russian authorship.

Like, we’re not even going to touch on Lenin and Stalin and the 1997 film Anastasia. As much as I want to! We’re going back to the 1800s in Russia, when tsars’ reigns bounced between huge reform, brutal imprisonment and crackdowns, and back again.

One hundred years earlier, Peter I, or Peter the Great, pushes for a rapid Westernization of Russia. The paradox to adopt European culture comes from a place of Russian preservation, a common theme with this quick adaptation. If Russia can match Europe’s innovation, they are better prepared to conquer and rule it. And, being an autocrat, the population has no change but to adapt to Peter I’s vision. As Hans Kohn writes,

Through [Peter I], Russia laid the foundation of great power and of an unbroken march of conquest in all directions towards an ever-expanding empire. Her subjects, however, enjoyed neither liberty nor law. They were reared, to quote the words of a great Russian historian, "to an atmosphere of arbitrary rule, general contempt for legality and the person, and to a blunted sense of morality." (emphasis added)

In 1703, Peter I moves the capital to the new city, St. Petersburg (named after, of course, himself). He mandates the nobility to speak, dress, and act like European nobles. Students are sent abroad to learn in Europe. By the 19th century, the nobility predominantly speaks French, not Russian.

His later successor and champion of the arts, Catherine II (a.k.a. The Great) encourages this scientific revolution and converses with European philosophers Voltaire and Diderot until the 1773 to 1775 Pugachov Rebellion. This uprising challenges her abstract ideals, and she responds with a clenched fist. For example, she orders the execution, mercifully altered to a Siberian exhile, of writer Aleksandr Raischev. The author of A Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow (1790), Raischev wrote critically about his travels through Russia and its serfdom.

Through this century leading to the Russian renaissance, Russians are inundated with hundreds of years of Western theology, philosophy, literature, and science. This creates a historic rift and a dissonance for Russian writers. As their education encompasses European history, they have to leave behind the isolationist past of their previous Russia. They adopt Western styles to preserve their Russian culture. As Tolstoy wrote about War and Peace, “There is not a single work of Russian artistic prose, at all rising above mediocrity, that quite fits the form of a novel, a poem, or a story.” In short, the Russian commonality is that it belongs to no form—though from this period, Formism and the emphasis of form as an indicator of literary quality dominates Russian criticism.

Curious about what’s happening in 19th century Britain during this time? Read history through Austen, Brontë, & Dickens:

By the 1800s, a golden age of poetry arrives with Aleksandr Pushkin (1799-1837), “the father of modern Russian literature.” In this century, we have Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910), Nikolay Gogol (1809-1852), and Anton Chekov (1860-1904), to name a selective few.

While this time in history is globally unprecedented for the high volume and quantity of authors in a region, these authors existed within this grey area of the deluge of Western literature while trying to create a new Russian identity.

In no other moment in history are so many writers producing such prolific works. This short-circuited history, to my eye, creates a systematic shock as writers conflate their past with their questions about the Westernized future. Who is Russian, what is Russian, and what is humanity in the wake of these reckonings?

There are three distinguishing traits of this era:

First, Russia considered literature incredibly prestigious compared to Europe. Dostoevsky even stipulated that literature justifies the Russian people’s existence.

While Europe had dedicated schools for theology, psychology, or philosophy, Russia’s writers had the responsibility and opportunity to bundle all of these ideas into their fiction. Dostoevsky’s novels specifically become foundational to the Russian identity as the intense psychological portraits and his theology become widely consumed and appreciated through his novels. As Encyclopedia Britannica writes, “One can see why the highest achievement of Russian literature was probably the philosophical novel.”

Lastly, politics and literature in the 19th and 20th centuries are intimately connected. Writers, like Dostoevsky, have the opportunity to become political prophets.

Though Dostoevsky grew up in a rapidly Westernized Russia and sought to become a writer during a Renaissance, his contributions as someone directly impacted by its poverty and imprisonment and nationalism comes to define this astounding period of world literature.

So, who is Fyodor Dostoevsky?

Born in Moscow in 1821, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s family came from poverty. Compared to Tolstoy or Ivan Turgenev, Dostoevsky did not come from landowning gentry class, and he felt poverty’s squeeze throughout his childhood and later in his adult life as a gambling addict.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to self-taught to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.